DANCER turned academic Dr Sandie Bourne, says the existence of Black dancers in British Ballet has been “wilfully ignored, downplayed and actively contested” and disappears as dancers die. Here Sandie and Marsha Lowe, Directors at Oxygen

Arts, discuss chronicling this disappearing past and how to use it in an activist present.

EXCAVATING what is left of the history of Black dancers in British ballet has relied on real human resources - the dancers themselves. But at times it has also relied on the memories of archivists whose institutions have lost track of,

or never kept their Black histories.

“It’s important to make clear here that the presence of Black dancers in British ballet was often wilfully ignored, downplayed and actively contested until relatively recently. So we know we’ve lost a lot of that history already”, says

Dr Sandie Bourne, a dancer, choreographer and academic specialising in the historic under-representation of black artists in British ballet institutions.

Dr Sandie Bourne

Marsha is working with Sandie on the Black British Ballet project, which now has exhibitions and events running in public libraries across the UK.

She said: “One of the driving forces behind our sense of urgency in this project is that many of the dancers are getting older and we wanted to record their experiences while we still had the chance. We managed to get Marie Kamara, who

danced with Les Ballet Nègres in the 1940s, on film just a few months before she died. But dancers like Johaar Mosaval who was in the Royal Ballet in the 50s, Henderson Williams and Jay Skeete who were at Dance Theatre of Harlem, and

Richard Majewski who performed around Europe, all sadly passed before we got the chance to interview them.”

Marsha Lowe

Human search engines

Sometimes information about these dancers exists in institutions but can’t be found. When this has happened, Sandie said, “human search engines” stepped in. “Often, we found that we were being referred to one or two people (with memories of steel!) who

had worked there over many years and amassed a huge amount of institutional knowledge. However, outside of these human search engines, cataloguing and maintaining accurate, accessible records remains hugely resource intensive and so, beyond

the means of many arts organisations.” Examples included Jane Pitchard at the V&A who offered to escort them around the English National Ballet archives “because she knew precisely how complicated these could be to navigate”.

Similarly, at the Library of Birmingham, which houses the archives for Birmingham Royal Ballet: “Of the four dancers we knew with a connection to the company, they could only find assets for one, Evan Williams. They did inform us that

this was because the collection wasn’t properly catalogued, and we encountered similar issues when approaching other major ballet institutions.”

Contemporary problem

The problem is not just a historical one and the project explores the historic challenges dancers faced but also looks at the current industry. According to Marsha, “Today, just three of the 233 dancers in the major ballet companies are

Black British” meaning the findings of Sandie’s research were “too important to remain within a thesis and had to be communicated more widely to drive change within the industry.”

The key findings were:

1. Ballet remains institutionally racist, with outdated perceptions of the Black body being unsuitable for ballet still prevalent.

2. Black dancers in ballet are poorly documented. Ballet institutions have limited documentation of former Black students or performers.

3. Black people in ballet are represented earlier historically than expected, with examples of blackface in the 16th and 17th century.

Performing arts in history

Performing arts don’t feature heavily in mainstream art history, and within the history of performing arts, dance is not high in the pecking order. Marsha said: “You’d probably have to separate out the performing arts, as theatre and opera

are quite well documented, but then you have costumes, scripts and scores that you are able to preserve. Dance is harder because the choreography can only be recorded in Benesh or Laban notation for future artists, which is not a language

that is universally understood outside, or even inside, the industry. Video has changed some of this but, like images, you then come up against issues around rights holders and privacy law, especially if you want to make such material

available online.”

Sandie adds: “In university libraries, dance of any kind usually occupies quite a small proportion of texts. Ballet tends to have the biggest selection of books, followed by modern/ contemporary dance, international dance, then African

and Caribbean dance and/or dance of the African Diaspora. This is changing slowly as now there are more books on Black dance and ballet. When I first started dance training in the 80s there was one - Black Dance: From 1619 to Today

by Lynne Fauley Emery (1972).”

She said the lack of material – and the lack of proof that any material even existed – made the tools of conventional research almost useless, and the discovery that it was “incredibly difficult to research the history unless you have

a background in the industry.”

Human Contact

That significant realisation, for both her dance and future academic career came in the 1980s when, during her dance training, she attended an open day with Arthur Mitchell’s Dance Theatre of Harlem at the London Coliseum. She said: “Surrounded

by 200 of my peers, for the first time I had confirmation that there were a significant number of Black dancers who were performing ballet. Without this certainty, and the personal contacts I made during my career, my research would

have been almost impossible to get off the ground. The few dancers I knew, introduced me to other dancers they knew, and so on, until we reached the 30 who are now featured on the website.”

US vs UK

Because of the establishment of Dance Theatre of Harlem in the 60s, where so many Black British dancers either trained or worked, we now know more about their experiences in the US than their earlier experiences in continental Europe adding

“our constant fear is that there are still dancers out there that we know nothing about.”

Examples include Dr Patrick Williams from Trinidad who was refused by the Royal Ballet School in 1965 because he was Black but went to New York, joined the Alvin Ailey Dance Company, was headhunted by Rudolf Nureyev at Paris Opera, eventually

returning to the UK, five years later, when all the major UK ballet companies wanted to work with him.

Or Carol Straker who was the only Black student at the Legat School of Russian Ballet and went on to train with Dance Theatre of Harlem. She had a long and varied career and after returning to the UK to find little had changed, she founded

the Carol Straker Dance Foundation in 1987 to support more diversity in dance.

What’s happening now?

The Black British Ballet project is both preserving history and campaigning for an equal present. It follows in the footsteps of pioneering examples like the Black Dance Archive project (2014-2018), which highlighted both the urgency to

record and the importance of making the history accessible, which it did through Black dance companies, individual artists, and academic institutions.

But Marsha said: “This type of cross agency collaboration is rare” and projects like Black British Ballet create archive resources from the sources they have available. “For us that meant interviewing the dancers themselves and allowing

them to share not just their experiences in ballet but also how their views on the art form have evolved over the years. But we’re not the only ones,” she says, pointing to Theresa Ruth Howard’s international digital archives of Black dancers in ballet,

Leon Robinson’s Positive Steps and Serendipity in Leicester, which have worked to archive Black British dancers and artists in general.

Personal history

Enjoying the arts and campaigning to make them more accessible were closely bound into Marsha and Sandie own experiences of being inspired but also excluded by the arts.

Sandie said: “I was interested in taking dance classes because my neighbour who was Black, and then my sister, started dance classes. I became aware of my race at secondary school in Essex, when the Alex Haley series, Roots, was televised

and the children at school called me Kizzy, the daughter of the slave. At dance school the teacher would ask me why I wasn't good at tap dancing, and I did not realise until later that she only assumed I would be because I was Black.”

Marsha said: “Growing up in the 70s and 80s, I always enjoyed reading and writing but the idea of becoming a writer had simply never occurred or ever been presented to me. However, my real awakening to the impact that race has on my understanding

of the world came when I studied at a US university. It was that first time that history had been presented to me from the perspective of the formally colonised rather than the coloniser, and it was a revelation.”

And while documenting Black ballet history Marsha said: “the clearer it became that we needed to do more.” The first addition to the project was a children’s book aimed at ages beginning their ballet training. The ballet show, Island Movements followed which Marsha said: “We created to push the boundaries of what a contemporary, diverse ballet could be, and root it squarely in the Black British experience.”

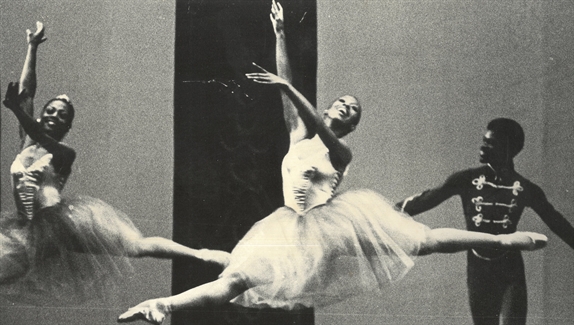

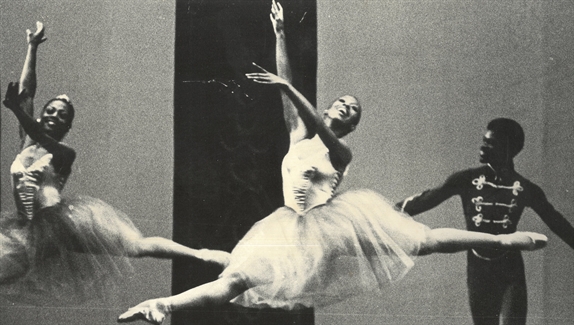

Island Movements © Oxygen arts

Public libraries

The show “would not have been possible without the involvement of libraries, who responded so positively to our call for venues to host the show, before we had a penny of funding in place.”, Marsha said, adding: “Working with public libraries

on this project is a complete no-brainer. Their spaces extend across the country, their staff understand the importance of telling these types of stories and immediately grasp the impact on communities that these could have.”

She said: “More and more though, people are beginning to realise that Black history is something that should be studied year-round and, in libraries, we already see the impact of that” particularly seeing Black British history engaged

with, rather than the US-dominated stories. But she said the change is happening far slower in other British institutions like schools and colleges.

Into the Light: Pioneers of Black British Ballet exhibition by Libraries Connected and Oxygen Arts is touring libraries until November

2025, funded by The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Top image: Brenda Garratt-Glassman in Fete Noire at Dance Theatre of Harlem ©1974 Photographer Martha Swope. Image on newsletter Denzil Bailey © Arena Pal photography by Simon Rae Scott

Dr Sandie Bourne

Dr Sandie Bourne Marsha Lowe

Marsha Lowe

Island Movements © Oxygen arts

Island Movements © Oxygen arts