THE appetite for horizon scanning among public librarians is huge – as we have recently seen at the CILIP Conference – but the number of public librarians paid to do it is minimal.

“There really aren’t many of these types of roles,” says Luke Burton, Director, Libraries at Arts Council England, “There are only a handful of national roles for example, at Arts Council England, CILIP, Libraries Connected, the British Library and DCMS. We are in a privileged position to be able to support and advocate at a national level.”

At the local level senior public librarian roles often focus less on public libraries and broaden out to include other sectors and professions.

“For me the next progression would have been outside of the library world. I was already responsible for quite a lot of stuff that wasn’t libraries: playgrounds, churchyards, rec grounds and maintenance of green spaces. In order to progress I would either wait for an opportunity to become more generalist within the council I worked in, or look for something that was more libraries focused.

Luke Burton

Luke Burton

“Getting this job was a progression to a national role that gives me a lot more time and space to digest and understand the strategic side of the sector.

“As a head of service you don’t have that time, you spend so much of it dealing with budget adjustments, staffing issues, support teams, and just leading your organisation. And that’s part of our role at the Arts Council, to do that horizon scanning for the sector and then try and put that on the radar of people who are living services day-to-day.”

In the blood

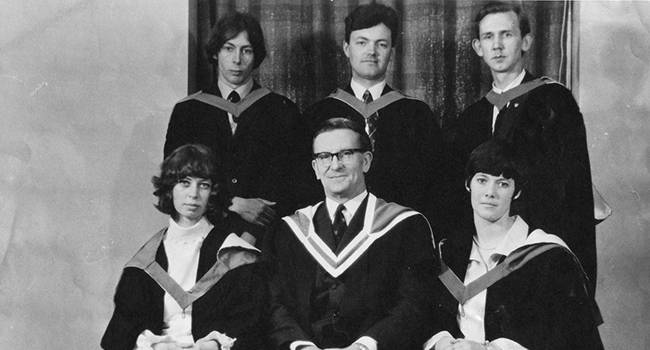

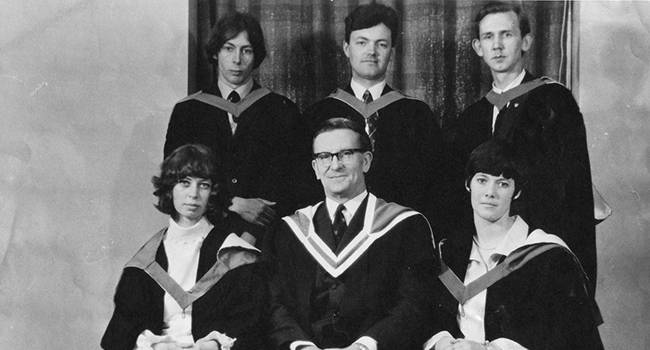

Luke’s route into librarianship might appear inevitable. “Both my parents are qualified librarians. They both graduated in 1969 as two of the first librarians to qualify with a BA from Strathclyde. Mum and dad both worked in academic and public libraries. Mum then spent the last 25 years of her career as a school librarian – in the secondary school my sister and I went to just outside of Glasgow. Dad was a lecturer in library and information management at Strathclyde and I still meet people who worked with him or were on his course.”

Luke’s parents, Lindsay Burton (front right), and Paul Burton (back right) were also librarians.

Luke’s parents, Lindsay Burton (front right), and Paul Burton (back right) were also librarians.

But despite his library roots, his first career was archaeology: “It was a bit like being a glorified student. It was good fun but for saving any money and putting roots down anywhere, it was more difficult.”

In his late 20s he decided to retrain. “I remember having a conversation with my mum one Christmas. I said ‘Don’t be angry but I think I might retrain… I’d like to work in libraries’ and she said, ‘Why would I be angry?’.”

Asked how his parents might have influenced him, he said: “I saw the real impact and benefits of the work that mum did in a school library. Yes, I saw that she had loads on her plate, but I think the role that the school library played at the heart of the school, that really had an impact on me.”

Career path

Choosing a route into the profession was done almost by chance. Luke says: “I went through the traditional route, library school, got a degree, got experience as a library assistant, got a job as a librarian, got my first management role and progressed from there.”

It sounds linear, but asked why he went for the public rather than the academic librarian route he put it down to “just doing what was available,” adding: “I did my two-week placement in the prisons in County Durham then ended up volunteering in prison libraries. And when a paid job came up, I worked in prison libraries, which then got me the role working in local studies libraries.”

He doesn’t remember making a conscious choice, but he acknowledges there “may have been a slightly subconscious leaning toward public libraries because they were such a big part of my growing up and I saw the potential to have an impact. Once in public libraries, that’s where I felt comfortable.”

Blocked view

Luke’s point about the dearth of national level roles is an acknowledgement that the sector’s resources for in-depth horizon scanning are limited. It also means that those institutions that do it, need to make sure their horizon scans are shared with all the professionals in the sector for whom it is relevant.

Luke says “When I got the job here at Arts Council England as Director, Libraries, one of the requirements was to have experience as a head of service. So even though I might quite quickly forget what it’s like to be a head of service, I’ve still got that understanding…”

His point is that there is still an advocacy job to be done to get the message across to library services about what Arts Council England can do for them.

“There is still some work to be done internally because the Arts Council has ‘Arts’ in the title. Because of the variety of ways that library services are managed within local authorities, some (library) services don’t see us as a natural first port of call for support. In Newcastle, we were part of operations and regulatory services. We came under school meals and bins and enforcement. We were much more operational. But if you come from a service that sits within the cultural or the heritage element of the local authority you might be more likely to look to the Arts Council.”

Clearing the view

Luke says Covid boosted the Arts Council’s profile across services, pointing out that: “Things like the Cultural Recovery Fund and Libraries Improvement Fund that the Arts Council administered for DCMS put us on the radar a bit more for some people who didn’t know about us. But there is still a piece of work to demonstrate our relevance and support that we can provide for library services.”

He said this is being achieved through “a change of emphasis from grant giving to development. The Arts Council is doing a piece of work on repositioning itself, moving from being a grant giving body that does development work, to being more about the development work and making that the priority, while also administering grants.”

Although the grants side may now get less emphasis, he pointed out that the Arts Council grants have expanded beyond purely cultural to cater for the wider remit of public library services. So library services that don’t identify so strongly with the ‘arts’ will connect more with development agency side and still find value in the grants. “There are some things that libraries can do that other disciplines can’t do” he says. “They can apply through the Universal Library offers for support that goes beyond just the cultural offer: they can apply for funding to support digital inclusion or health and wellbeing.”

Gap filling

These funding streams illustrate the mission creep that has been going on in public libraries since they first existed. The sector’s habit, or role, as a gap filler is a problem, but also an opportunity.

He points to work the Arts Council has funded CILIP to deliver which looks at the future of libraries particularly after they “demonstrated their adaptability during Covid and their ability to identify the needs of a community and then fill the gap.”

He said: “It is what libraries do, and we have done that for time immemorial, whether it’s PCs or warm spaces (which libraries have provided since the 1850s) or digital skills, libraries have filled those gaps.

“But it’s not necessarily a sustainable way for libraries to operate. The sector has an ability to adapt on a short-term basis – the question is how to turn that into a long-term benefit?”

He says that modern libraries are supported by a system that is too old and slow to acknowledge what the sector does. “We’re essentially still working in a Victorian model and even if you look at what the 1964 Act requires from local authorities, there’s a whole wealth of activity that sits outside that statutory provision. This is where libraries have stepped into the gap. But how does that play out, what will their role be in 2030 or 2050?”

More unique skills

In local government a senior role now means less focus on a specific sector while, on the ground the opposite is happening. The sector’s USP – low barriers to access information – is becoming clearer but the skills required to apply it are increasingly diverse while remaining unique to the sector.

“That’s where public libraries have a unique role to play, as that safe space with soft skills and people skills that help their communities gain access to anything – whether it’s access to technology, cultural activity, health, wellbeing, support, business support. They have that lower barrier – it’s less intimidating to get business or financial information at the library than the bank, or health and wellbeing information rather walking into a hospital or a doctor’s surgery, it’s helping people on those journeys.”

The low barriers mean they are good at filling gaps. But it also means they need people with the skills relevant to those particular gaps.

“Because libraries do so much, you’re looking for a range of skills and experience. You’re recruiting frontline staff who could be dealing with anything, or people who are developing services and programmes.”

He said that the range means that different services are becoming more specialised in particular areas. “There ends up being a focus. Some library services have real strength and skill around health and wellbeing or working with their public health teams. Other people have a real strength around heritage and culture, other people, it’s customer service and digital.”

“The question is how do you then provide people working in libraries with these skills? Yes, the buildings are brilliant and the infrastructure is important, but it’s nothing without the people.”

So far the sector has managed to meet these challenges but the aim is to make the processes for gap filling more coherent and sustainables.

Consumers or creators?

AI is a ‘live’ example of how a changing world will put pressure on public libraries to fill more gaps. Luke thinks the impact of AI is much “clearer or much more concrete for people in knowledge management and academia in terms of what it’s going to do for them. For public libraries though, it feels as if there’s definitely a role for their softer skills.”

He sees libraries filling the immediate gaps, as they always have done. That has ranged from how to set up an email account to providing code clubs. With AI he thinks they will have a role in helping people “understand what they’re asking it (generative AI), how it’s coming to its answer and being critical about and what it is that comes out. So, I think public libraries have a role to play in providing a safe space for people to do that.”

That’s just one example of a gap, the question is how to turn that gap-filling power into a sustainable business model. With the AI example, yes there are lots of interesting risks and opportunities that libraries can help communities address, but Luke says: “The danger with AI and other emerging technology is that libraries end up as consumers of content rather than creators and owners of content. They just end up licensing products. The question is how can they actually be involved in the creation, testing, building and implementation of AR, VR, artificial intelligence, emerging technologies?

“It’s challenging for librarians to contemplate a question like this when they’re trying to do the day job. That’s where the Arts Council comes in as a sector development organisation. How do we equip libraries to be on the front foot when it comes to those things? To have sight of what’s coming”

Convenors of soft power

“It’s back to that advocacy piece, that libraries aren’t always the answer, but they are often potentially part of the answer or part of the solution. If it’s new and emerging technology, how do you ensure that it’s people centred? How do you ensure that it’s accessible? How do you ensure that it’s fit for purpose? Public libraries are often the only community or public facing space in a community.”

He gives recommendation lists and personalised reading lists as an example. “Being able to say ‘you’ve read this book, so you may like that book’ is something that libraries are interested in. It is a form of AI or certainly a form of machine learning. And projects like Ask For A Book, which Leeds library are leading on – and is one that we’re funding – is a recommendation tool. But there’s an actual human behind that part of the process so there’s still the library skill in there being promoted alongside the machine.”

He says that potential lies in bringing technology-rich parts of the public sector into contact with human-rich public libraries.

“For example, Leeds University has access to technology that a library service doesn’t have the resource to buy. But by coming together you can provide access to the audiences and the soft customer skills and bring that technical expertise alongside it and work in partnership.

“It’s an aspiration we’ve talked about, to broker relationships for library services that don’t have the resources with the academic sector and the public sector – talking to people about what it is that they’re trying to do and building relationships through the libraries across cities like Leeds.

“The Arts Council can support public facing projects that support communities, we’re also keen to understand where there are R&D gaps in the sector and between organisations in the sector, and how can we help.”

Luke Burton

Luke Burton Luke’s parents, Lindsay Burton (front right), and Paul Burton (back right) were also librarians.

Luke’s parents, Lindsay Burton (front right), and Paul Burton (back right) were also librarians.