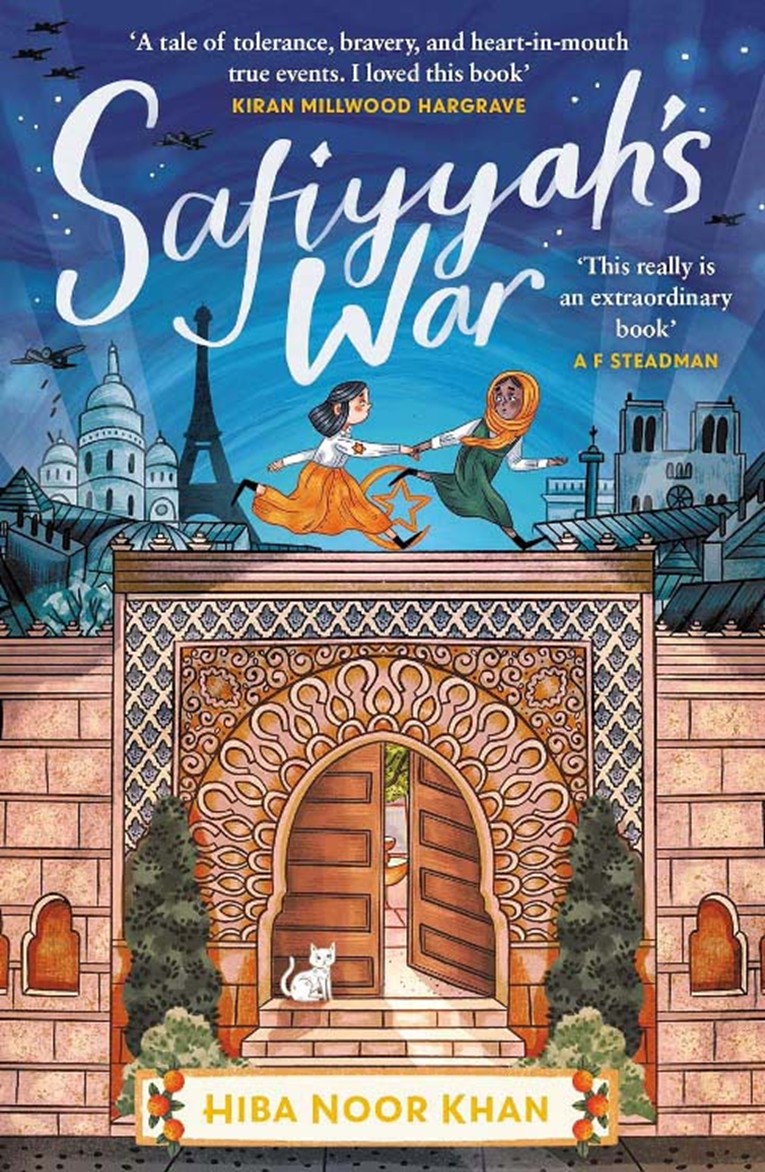

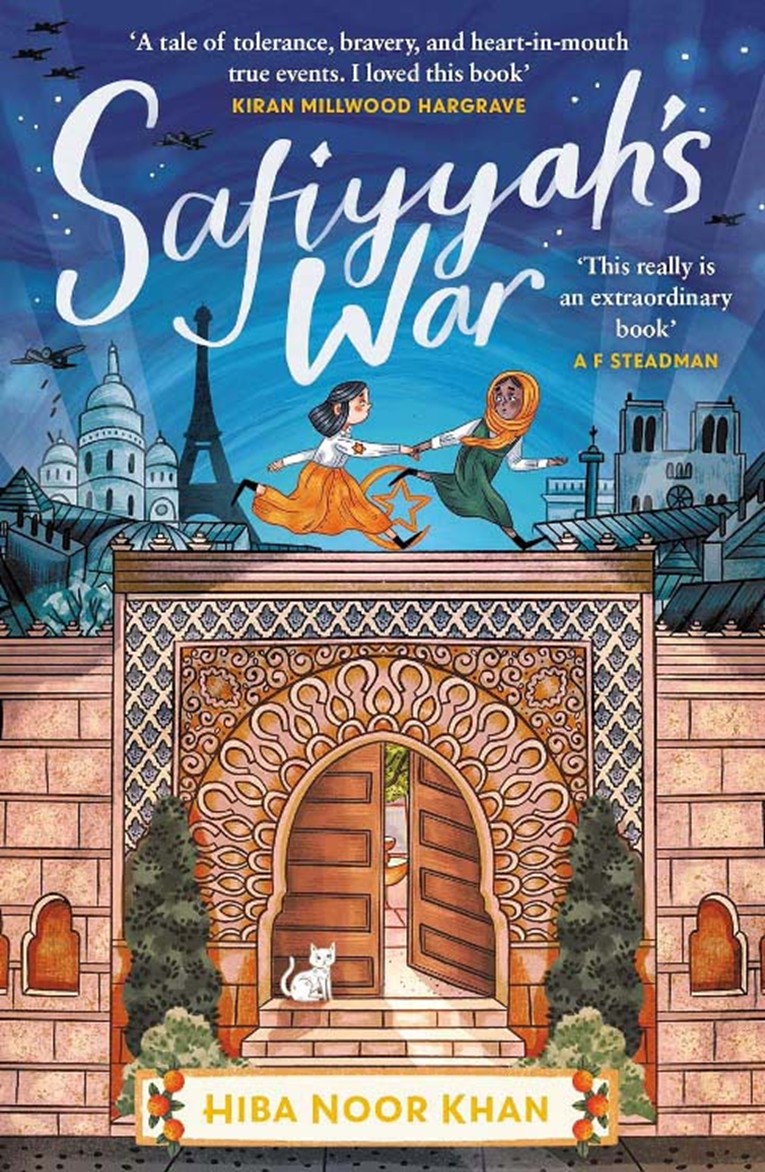

Hiba Noor Khan’s creative journey began with a love of words and a deep-rooted curiosity about the world. This desire to question and look beyond the obvious has enabled her to shine a light on lost truths. Shortlisted for 2024's Carnegies

Medal for writing, she talks to Rob Green about what inspires her to write.

WHAT lies beneath is often more important than the surface that we see. The hidden depths in life are where the real interest is, and so it is with Hiba Noor Khan’s Carnegie shortlisted Safiyyah’s War.

The tale is grounded in a real-life story of heroics and danger set in Paris during World War Two, yet unlike many similar deeds this one has largely remained obscured. It is fitting that Paris’ deep network of catacombs provide a setting

for Safiyyah’s War – depth on many levels; hidden and out of sight for too long.

The story of the Grand Mosque in Paris and the role of the people who worshipped and worked there during the time of the German occupation of France is truly inspiring… and yet it is not widely known. Hiba says that despite her own Islamic

faith she was not aware of how Muslims in the City helped their Jewish neighbours escape Nazi persecution.

And so, when she first learned about the bravery of the Mosque’s Rector Sidi Abdel-Qadir Benghabrit, plus the countless other people who were involved – including the Imam whose name is lost, she could scarcely believe that she had never

heard the story before. She says: “I had never heard this story. I had studied World War Two in school, I’d read the novels, watched a lot of films and thought I knew what went on. But when I came across this story three years ago

for the first time, I thought ‘is this real?’ I began to research it and as I discovered more, I just sat at my laptop and wept for 15 minutes. I was so awed and inspired, but also so surprised that I hadn’t heard this story. I went

to all my friends and family, and no one had heard it. I have met maybe one person who knew it.”

So, what exactly was the story that had been buried? Hiba explains: “Safiyyah’s War tells the real-life story of the effort s and resistance of the people in the Grand Mosque in Paris and their commitment and bravery saved the lives of

hundreds and maybe thousands of Jews.

“The book features various real-life figures. One of the main characters is Sidi Abdel-Qadir Benghabrit, who the book is dedicated to. He was the rector in the mosque and the main man behind it all. Along with the Imam who we don’t actually

know what his name is. Together, and with their community, they would bring Jews into the mosque and provide them with false identity papers that showed them to be Muslim. The Muslims weren’t being persecuted in the same way at that

time because of the politics around Hitler and the colonies in North Africa that he was planning on taking over.

“They had the authority to issue identity documents as leaders in the Muslim community, and they were doing this and distributing them. As things got worse, they would bring Jews into the mosque and they would hide children amongst their

own children. They had 10 apartments in the mosque for staff members and the adults would be able to hide children around the mosque.”

“The mosque was located above the Subterrain in Paris, the miles and miles of tunnels that run beneath the city. So, they used these tunnels to smuggle many Jews out through the basement and through the tunnels where they would come out

near the river and smuggled out of the city on boats.”

Hiba adds: “I felt this immense sadness and sense of anger that this has been forgotten and swept away because it doesn’t fit in with the convenient narrative.”

Current affairs play out in the telling of this 70-plus-year-old story today. There is no escaping the division that is being spread both at home and in the wider world. Often it is too easy to accept the predominant narrative, and there

needs to be deeper exploration to get to the truth.

The war in Gaza feeds into a notion of Muslim against Jew, and Jew against Muslim – yet there are countless counter narratives that dispel this simplistic world view. Safiyyah’s War is just one of those many stories, and Hiba

says: “It has been very strange in the sense of the timing with everything going on in Gaza. It feels very painful – I wrote in the dedication ‘for every child of war, may you be the last.’ It’s a World War Two setting and the children

are experiencing war, but here we are in 2024 and one in five children are impacted by war around the world – and that is unfathomable.

“This story of shared Muslim and Jewish history. For many people, this vision of Muslims and Jews together can only bring visions of conflict and war. But this story is just one of countless instances in which the opposite is true – Muslims

and Jews have lived together in cities, and lands form Jerusalem and Andalucía and various communities around the world. We are being fed reductive and polarising tropes and the rate and intensity of that is increasing. I think literature

like this can be a humanising force, and needs to be a humanising force.

“I hope the novel challenges those conventional ideas. It tells the story of a resistance mission of those in the mosque, but just telling this story is also a type of resistance against the erasure and the narratives we are being fed.”

Safiyyah’s War is not the first time Hiba has explored the notion of erasure and hidden truths as an author. She came into the profession via a circuitous route that took in science, teaching, refugee advocacy, sustainability,

and diplomacy – driven by a curiosity and desire to challenge convention, but always with the written word as an anchor.

She says: “In terms of my journey to actually becoming a writer, and looking back, it had always been central to who I was and the way I process the world from a young age. I remember that words as things, as a concept, as entities were

important. At a young age I was a deep thinker, and I took in quite a lot and absorbed quite a lot, and at points I really struggled to exist in the world and to navigate the world without words. At a young age it was subconscious,

and it became more conscious to me that the world is strange and beautiful, but also ugly. It can be full of light, but also darkness, and it can feel quite chaotic at times. For me to process and deal with this weird and wonderful

and tragic and illuminated space, would be impossible without words.

I had a grounding ritual of writing in my diary from about the age of six and also writing stories from a young age. Stories were very innate to me, there was this tangle sometimes with myself and beyond myself – words felt like this empowering

means to pull threads out of that tangle and to start to pull and to work with them and weave with them and create something that made it all make sense somehow.

“I was writing poetry, and my first poem was published when I was about eight, and it was called Need or Greed and it was about the environment. I was a writer in the true sense, the words were in my blood and in my bones, but I didn’t

realise I could do this as a profession. So that was why I went to look at other courses and fulfil these other interests that I had. It was probably only the last couple of years that I realised, OK maybe I can do this.”

That realisation came following what might be considered a fairly mundane route of answering an advert and submitting a CV. She says: “I had this distant dream of writing a novel, maybe a cathartic or therapeutic process, rather than this

going to be something that sells in bookshops. It was literally just me pulling out these threads of chaos that I was witnessing around me and form within me. Initially it was really adult publishing that seemed most likely.

“I had followed various bits and pieces from publishers on social media – there was a curiosity, rather than being really driven or even being a realistic option for me. But there was an open call from Puffin as they were launching their

Extraordinary Lives series and you just needed to send in your CV. I had dabbled in some freelance journalism which was another outlet for me. But I did send my CV on a whim and heard back, and they invited me to do some sample writing.”

That led to Hiba being commissioned to write for The Extraordinary Life… series of books, and the story of Malala Yousafzai. Following that release, Hiba returned to her science and engineering roots – she had studied engineering at university

and gone on to become a physics teacher. Her two follow-up books, How to Spaghettify Your Dog and Inspiring Inventors who are changing our world both touch on hidden depths in different ways.

She says she wanted children to see the beauty, wonder and mystery in physics, something she felt was missing from the way science is taught in schools, adding: “It is mysterious and bizarre and brilliant and surprising and fantastical.

It’s almost a magical realm – and I thought people were growing up and missing out on this. There’s a collective sigh when you mention physics, but I used to stay up late thinking about quantum physics and writers who loved it in the

same way as I did. And I thought children are missing out on this incredible world, so by combining creativity with a bit of silliness we got something really unique.”

Incredible inventors… is even more explicit in its exploration of the hidden stories around technological developments – stories that are often deliberately obscured and pushed aside. Hiba says: “Living in a world driven by capitalism,

the drive is on everything being faster, stronger, quicker, more convenient and we are hurtling towards this vision for life and what human existence should be at speeds that now one can really grasp.

“I felt very frustrated with this paradigm for science and technology, and I was fascinated by the idea of progress and how we talk about progress. Often that tends to be without heart, humanity or ethics – it’s just a drive towards convenience

and ease for the wealthy in the world. I did a lot of research into people who harness technology and science for the betterment of the planet – for people who are struggling with water issues, or poverty of disabilities. I wanted

to redefine what we think about when we talk about progress. I felt a bit disheartened by it all and wanted to show that there are these really beautiful creative innovators.

“A lot of the time they are harnessing indigenous wisdom and ancient practices and knowledge to protect and preserve, so there is a focus on erasure as well. I think people who are not conventional inventors – people who are not white

men have been erased, through patents and other structures. You can look back through history and see examples, such as Amazonian tribes who pioneered surgical tools. It helps to give a more rounded holistic view of the world.”

Hiba’s next work will look at another under-reported piece of history that affected millions, yet remains out of sight. The Indian Independence Act of 1947 was designed to deliver independence in the former British colony, but it also

saw partition lines drawn across a region leading to mass migration and violence.

Hiba says: “The Line They Drew Through Us is another historical fiction book and is centred around the partition of India. It’s one of these instances from history whose echoes reverberate today, but it’s not taught in schools,

it’s not really mentioned much at all and when it is it is glossed over in quite a reductive, simplistic, and often unjust way.

“The cruelty of Empire, the treatment of India and Indians and the repercussions that has had on every South Asian who exists, both on the subcontinent and within the diaspora is very significant. It’s infused into our existence, even

though most of the people who have lived through the partition have passed away. It is something that if I had understood in a deeper sense when I was young would have been very empowering and important for me to learn about me, as

well as everyone around me learning about it. It would help us understand our place in the word in the country and help me understand some of the racism I grew up with.

“The line they drew through us is a story of hope and it’s a human story. There is this other aspect of what we are seeing with the rise of fascism around the world, including this huge issue in India around the Hindu-Muslim conflict.

It explores the relationship between Indians – the Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs as well as the role of the British and why things are the way they are now.”

The story revolves around three friends, each from different religious backgrounds, and how their lives are affected by the partition. Hiba says: “There is a need in me to seek justice, and whether that is bringing to light stories that

have been erased or overshadowed. Stories that deserve to be known; songs that deserve to be sung. And that might mean redefining things that have had the humanity and heart sucked out of them. There is this need in me and that is

echoed through all of my stories and all of my books. That ability to dig deeper and that desire to dig deeper is maybe one of the greatest gifts we can give to children.”

Although nothing is certain yet, Hiba’s next books could be delving deeper in the world of fantasy – revisiting her childhood love of Tolkien’s Middle Earth and C. S. Lewis’ Narnia. Watch this space.

This article was first published in CILIP’s Pen&inc. Autumn/Winter 2024 issue. To read more from Pen&inc. sign up here to receive your copies for 2025.