Copyright has created a digital dark age where the most powerful tools for cultural analysis are blind between 1910 and the rise of social media, says Melissa Terras,

Professor of Digital Culture at Edinburgh University and keynote speaker at CILIP’s Copyright Conference 2021.

Risk aversion is the issue that Professor Melissa Terras returns to again and again when she talks about copyright. She says that circumstances – financial, political and cultural – mean institutions increasingly resort to a blanket ‘no’

when asked to take any copyright risk.

As a data scientist and information engineer – rather than a professional librarian – is she just impatient with the sector’s tried and tested safety mechanisms? This could be answered by pointing out that she is CILIP chartered (she discovered

her own personal attitude to risk on a Naomi Korn copyright course), is a trustee of the National Library of Scotland, has taught library students at UCL, and chairs the Library & Information Systems Committee for Arts, Humanities

and Social Sciences, responsible for spending on library materials and systems across a third of the University of Edinburgh. But even if she didn’t have these credentials, her observations about the bizarre impact of copyright on

research should prompt institutions to reassess their attitude to copyright risk.

No blankets

“I think the blanket ‘no’ should be replaced by risk assessment” she says, “because this should be about institutions understanding their capacity for risk. They should ask “what’s the worst thing that can happen?” I’ve read that only

seven libraries have been taken to court in the UK. And if they’re more worried about reputational risk than the benefit they might bring to their audience, there is a problem. Because is it really copyright – the right of the author

– that you’re worried about?”

“Being on the boards of certain places, I can see that institutions are inherently risk averse. They don’t want any bad press, they don’t want to use institutional resources paying for lawyers, they don’t even want that conversation. So,

while the tension should be ‘yes there is copyright, and yes we should be respectful of creators’, that is not where we are now, we are in a state of paralysis.”

However, Melissa acknowledges that, right now, cultural institutions face a perfect storm: “The political and financial threats our institutions face are real. They are not just a perceived threat – it’s a very dangerous time to speak

up and rock the boat when you don’t even know if you’re going to have an operational budget next year.”

Bad environment

The problem isn’t just a sector on the backfoot. As chair of a university library committee, she has followed the current ebook pricing controversy and believes it is a symptom of a deeper problem. “They’re fleecing us. I understand there’s

a commercial opportunity, but this is during a pandemic. So, I think part of the problem is the way that commercial suppliers view universities as cash cows. Ebook pricing is symptomatic of many things that are wrong with the way the

information environment works around universities and research. How, in a world where we are all working from home, can the information environment be so locked down? It is the fear of copyright and the licences which are entered into

with the major suppliers. This is not just a research issue. It is a point of social justice. If you go to a rich university, you will have access to information that you can’t get at your local college.”

But it is in her own areas of expertise that she can describe the tangible impact of copyright restrictions and the fear around them. In an era when computers are learning to measure the influence of culture, copyright keeps the 20th and

21st Century off limits.

AI and the Romans

Melissa’s career path started off firmly in the arts. A revelation came when she was asked to present her undergraduate dissertation (on ancient Greek art) in a multimedia project. “That’s when I saw I should be doing computing. Before

that I was a bit lost. People were saying it wasn’t an area of academic study – that computing in arts and humanities wasn’t a real thing. But I saw that it was, like a truth of the universe.”

She turned this realisation into a reality, converting to a masters in computing science, followed by a PhD in engineering at Oxford. “At Oxford I was working in a group that did image processing – extracting information from digital images.

It’s very common now, with face and handwriting recognition. We were applying techniques used to interpret medical images to ancient documents, using them to read things that were too damaged for the human eye. A computer can take

each mark and say ‘this is likely to be a handwriting stroke’ or “this is likely to be wood grain” or “this is likely to be noise because it was buried for 2,000 years”. You pull out all the scratches and then run probability engines

over what is left, like a crossword puzzle. The big one we did that the historians were really excited about was a document proving that the Roman Army had road tax in northern Britain.”

The Digital and the Victorians

To read Roman artefacts computers needed a to be trained on a digital library of handwriting to see if a mark was part of a message or noise. Now, among the things that Melissa and her students use computational techniques for, is the

investigation of individuals rather than artefacts – to see how they have been influenced by culture. Instead of a library of marks, a conventional library of books – digitised in full – is needed and can provide insights that were

impossible in a pre-digital era. “I had a PhD student called Dr Helen O’Neill and she worked with the London Library, looking at their members’ books and registers. We looked at John Stuart Mill, the politician and economist, who was

an active member and donated a number of books. Helen compiled a list of all the books he’d borrowed from and donated to the library, and then we used large scale computing to mine that against all the books he’d ever written. It was

like a historical Turnitin (a web-based plagiarism checker). It meant you could find the influence of a library on an individual through his books. But to do this you need to have those lists of books and then it’s all contingent on

having access to the full text of these books. At the moment you can only do that on pre-copyright years. The guillotine falls about 1910. You can’t study anyone after 1910 using that because we can’t get access to full text resources,

unless you digitise them all yourself. The Victorians are the people that you can study because that’s when you first have mass print that’s all out of copyright. You can’t do it on the Edwardians, you can’t do it on the second world

war. No way can you touch the 1940s. So, we couldn’t easily do that same study on Virginia Woolf (as some of her works are still under copyright in the UK, and so not available for text mining, unless we digitise them ourselves).

Dark age

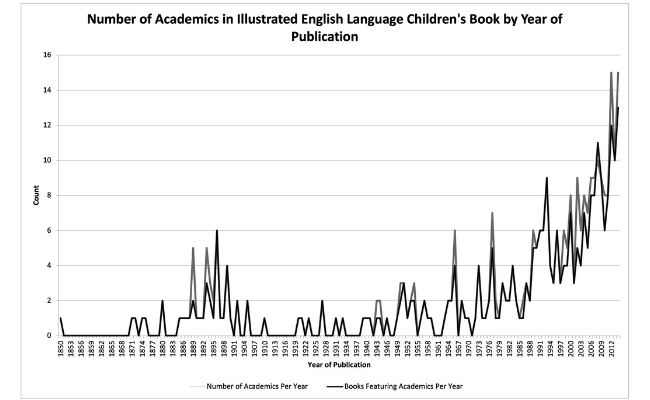

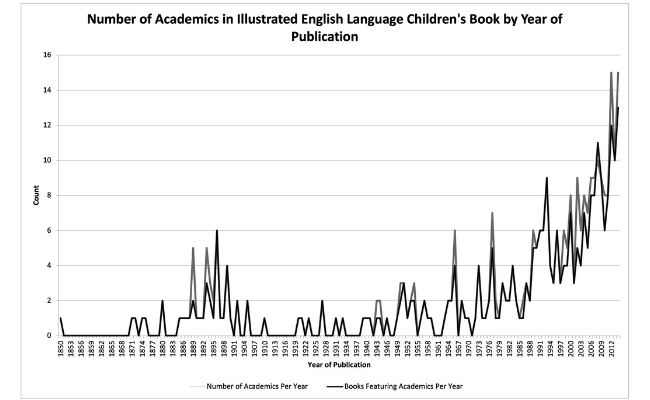

One of Melissa’s recent projects used text mining to find mentions of professors and academics in children’s literature. It provides a good illustration of the problem. “I have a nice graph which is about the number of professors in children’s

books and from about 1850 it rises and rises because I’m able to do full text searches across Google books and the Internet Archive until you hit about 1910. Then it disappears because you can’t search in the same way.

Your method has to change from doing full text searches across massive collections to actually doing a traditional bibliographic search, calling things up from the library and looking through yourself, and that limits scale to human.

It picks up again in 2010 because of Waterstone’s catalogue, ebay and Amazon. A similar issue would crop up if she attempted her current project in the 20th Century. The book will publish primary sources about women’s rights like

speeches. Here the text mining is used to hunt down references.

“You take a speech from a Tuesday in February in 1890 and the speaker is talking about what a politician said last week – no name just ‘the honorable gentleman said...’ and the audience laugh. It’s like someone saying “Barnard Castle”

now. “In a hundred years you’ll go ‘what’s that?’ Without these resources, this mass digitised content to mine against, I would be lost. But you can only do this against large-scale digitised content, which is bounded by the copyright

frameworks.”

Pay what you owe

Melissa acknowledges the problem is not a simple one to solve. “I’m not saying for a minute we should ride roughshod over creators’ incomes. Similarly I don’t agree with those researchers and academics who think because something is out

of copyright they have a right to see it for free.

“They need to be more respectful of libraries for looking after stuff for hundreds of years. I have dug up things where I’m probably the first person to see it for a 100 years. It doesn’t bother me that I have to pay a fee for that to

be digitised. The point is that I wouldn’t be able to find it without the stewardship of this library.”

She wonders if institutions might benefit more from opening up and trusting people’s good will. “What you get in libraries, for example in the BL reading room, are signs saying ‘you can take pictures for your own studies but it’s illegal

to use them anywhere else’, perhaps they could say ‘if you are taking our out-of-copyright stuff and using it elsewhere you might want to contribute back to this institution…’.”

Internet Archive

She also acknowledges the organisations on the further reaches of the sector and suggests more support for them when they push boundaries that most cannot touch.

“I love the Internet Archive and not just that they are pushing the envelope when it comes to copyright and permission and their cheekiness. They’ve built an incredible infrastructure that is amazing for researchers and I don’t think that

they get enough kudos. With their Emergency Library the voice of the publishers against them is very strong and we don’t have that same lobbying for researchers. But they’ve done some really interesting things, and have a completely

different attitude. I donate to the Internet Archive and to Wikipedia (and more people that use them should), or if I use an image or content from a library I make sure I make a donation. However, I realise this is a point of privilege,

that I have the resources to do so.” This all shows how aspects of copyright intersect with aspects of privilege, and how choices made regarding what is prioritised to be in the digitised environment is dependent on risk appetites,

affecting access for all. Melissa is still optimistic, though, about the potential of using digital approaches to study the past. “We’re only just getting started. And there’s so much more we – and the students and researchers coming

after us – will be able to do, given the digital cultural information environment is ever growing, as are the tools available to interrogate it.”

Copyright Conference, 10 May (Early Bird discount deadline 31 March) This year’s online Copyright Conference is an ideal and unique opportunity for all librarians, archivists and information professionals

to update their knowledge and professional practice in this crucial area. Additionally, it will appeal to those who want to update their general copyright, licensing and publishing knowledge.