Leading Libraries Series: Leading for Resilience

Emotional resilience

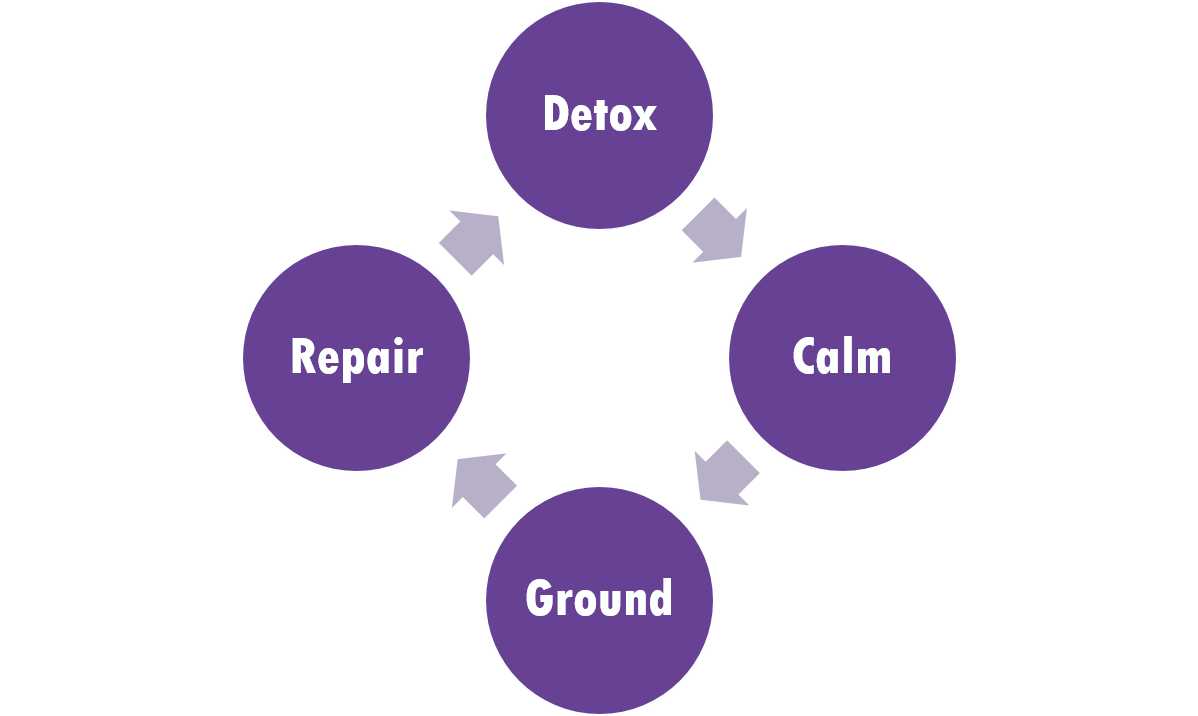

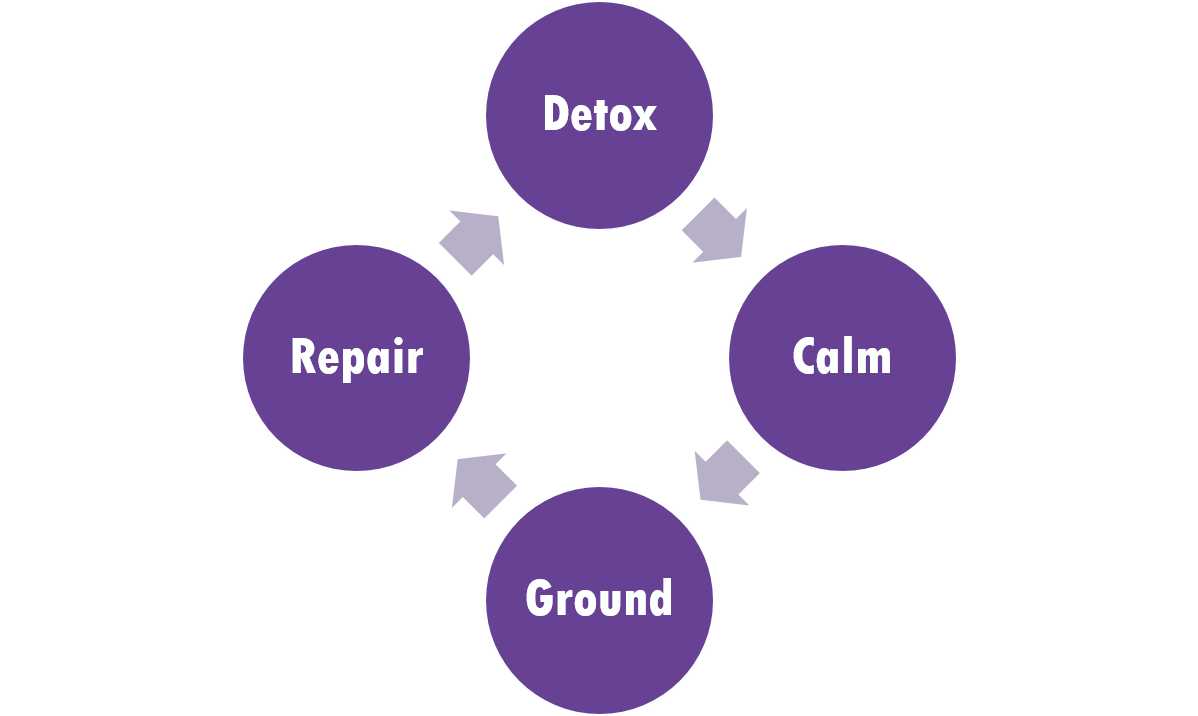

The recovery cycle

The ability to calm ourselves down is a key part of recovering from shocks but it is not always the first step! If you want to improve your resilience it is helpful to incorporate practices which cover all four elements of what can be described

as the ‘Recovery Cycle’.

Detox

Sometimes unfortunately, we cannot bring ourselves back to a calm state immediately. This is usually because the level of stress hormones in our body has got too high – we need to shift those transmitters out of our muscles and blood stream

before we can relax.

Animals in this state do one very sensible thing – they give themselves a very good shake! Shaking shifts the stress hormones by allowing our muscles to respond to the shock as they were designed to do and break those hormones down as a result.

As grown up humans, we are often reluctant to do this in public (for obvious reasons) but if we can find a private place to ‘shake it out’ this often opens a doorway to allow us to calm down. It is also a great practice at the end of the day

to detox ourselves.

Calm

The key move in calming ourselves is the slowing of the vagal nerve rhythm as described above. Slow deliberate breathing works really well for most of us – you can read more about why slow calm breathing works in this helpful article on 7-11 breathing from the Human Givens Institute.

If you find it hard to breathe your way into a calmer state, there are two other tactics that some people find really helpful. One is to ‘get horizontal’ – lie on the ground ideally – as the body is automatically less stressed in that position

and calms more readily. Surprisingly, our vagal nerves can also be calmed by resonating with another person’s (or animal’s!) vagal nerve rhythm – which is why hugging works as a calming mechanism (providing the other person is not anxious

too!). The positive effects of companion animals are becoming well known – and part of the reason for this is because they help us directly regulate our emotional state.

Many of us find that we also need to find ways to calm our minds (and especially our self-talk) as well as our bodies. The main aim is to shut off unhelpful inner dialogue (rumination) or self-critical messages. Often, it is enough to just

switch over to doing something you enjoy or focusing on another person who you like being around.

Many people find ‘mindfulness’ practices useful (although some of us don’t) and there are now a huge range of resources in this category on a range of websites. It is worth having a browse around to find a visualisation or meditation which

really works for you – preferences are very personal, so its worth trying a few different sources. The well known ‘HeadSpace’ app is used by millions of people as an introduction to mindfulness.

Ground

Once we have calmed our body and our mind we can begin the process of ‘coming back to ourselves’ and getting in touch with the world again.

The term ‘grounding’ is used in many ‘somatic’ disciplines like yoga and the martial arts – it means making contact with reality, settling into gravity, feeling ‘at one’ with our surroundings.

Shocks tend to make us ‘turn in on ourselves’ – grounding brings us back into our bodily experience and gets us ready to face our situation again.

Repair

Finally we need to make sure that we have done what we need to do to repair any ‘damage’ done by the stress hormones and other chemical imbalances created during the shock phase. The actions that are useful here are often the same ones that

our parents recommended when we had a shock as children – comfort food is really comforting in moderation!

The important thing is to actually do these simple actions – rather than putting them off until later or thinking that they don’t really matter! Another key practice is emotional reconnection, including with the person or people who

were involved in the upset. We can express our feelings more responsibly and effectively at this point and it often ‘closes the cycle’ if we allow ourselves to do so.

Quick fixes

For each element of the recovery cycle we have provided a two minute fix, including a fix which you can use in a Zoom call!

- Detox

- Fast fix: Voluntary shaking – 2 mins should do it

- Zoom fix: Drink water, clench and unclench fist or go on mute and tap your legs

- Calm

- Fast fix: 7-11 breathing (NOT deep breathing)

- Zoom fix: Unfocus your eyes and consciously breathe more slowly

- Ground

- Fast fix: Whole body tapping

- Zoom fix: Cross patterning (cross arms and legs in contact with each other)

- Repair

- Fast fix: Eat something nutritious and drink a calming tea

- Zoom fix: Aim to smile and talk a little more – in an informal or friendly way. Drink water again!

The fast fixes we have described above are great for emergencies but it helps your resilience even more if you have some more substantial 'practices' which give your body more of a chance to recover. There are some detailed instructions for

one 'practice' under the heading below - it's even better if you learn these physical recovery practices by using them regularly, even when you haven't had a shock to the system. Your body will gradually learn to regulate itself more effectively

over time.

Practices for when you have more time

The activities above are great when you are pressed for time, but if you would like to explore this further try out the exercises in the Recovery Cycle Exercises document.

Continue to: Building your own recovery practices